Programmation

Du 2 au 6 avril 2025

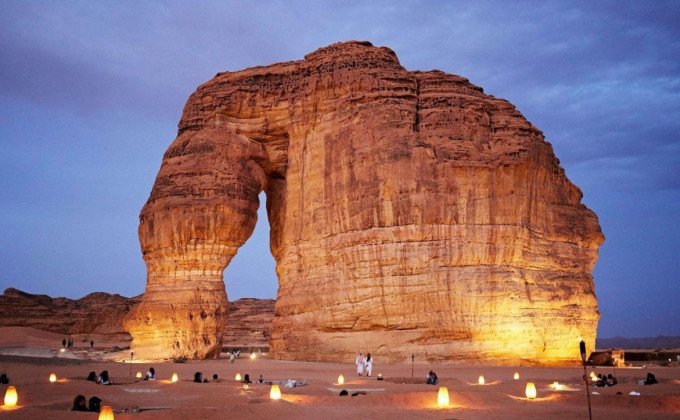

TEMPS FORT LIBAN 3/3 : FUTURS DU LIBAN

3e et dernier des 3 temps forts dédiés par l'IMA à la scène artistique et intellectuelle libanaise. Au programme, des séances d’écoute, des projections, des rencontres littéraires, des spectacles et concerts, pour mettre en lumière les dynamiques de la création et des pensées libanaises contemporaines.

Voir tout le programme

Le monde arabe pour tous

L’IMA met à la disposition du public des ressources et services adaptés à tous pour faciliter et encourager l’étude, la connaissance et la compréhension du monde arabe, de sa langue, de sa civilisation.

L'IMA vous donne rendez-vous

Magazine

Collections

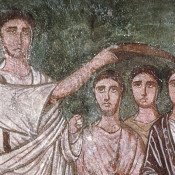

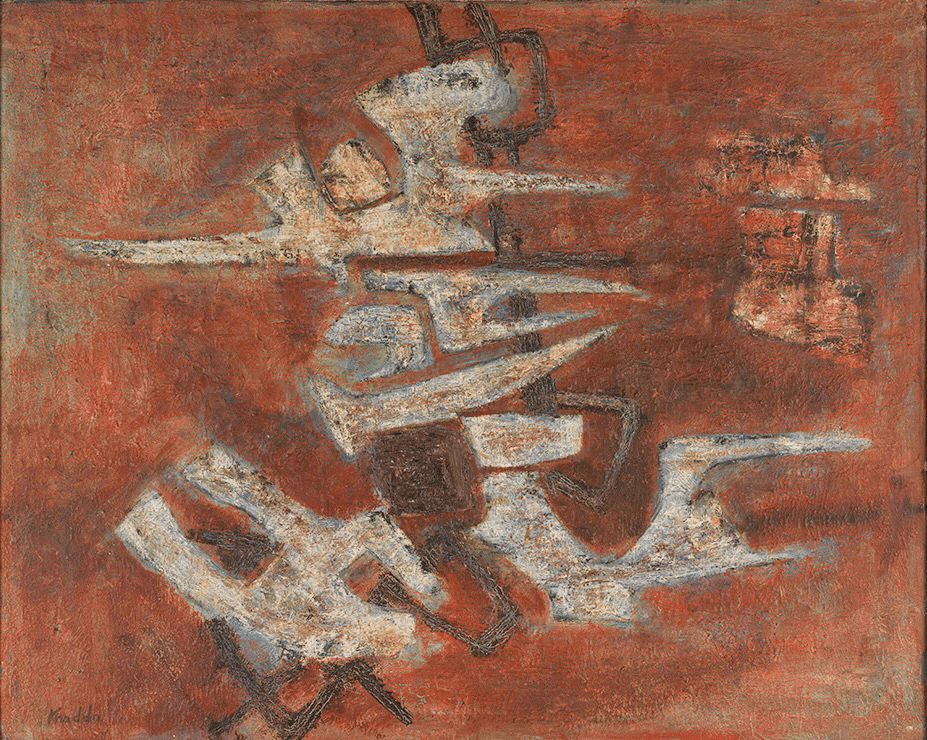

Mohammed Khadda, “Afrique, avant 1”

À découvrir dans le cadre de l'exposition “Paris noir”, au Centre Pompidou, jusqu'au 30 juin 2025En boutique

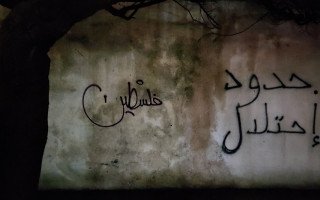

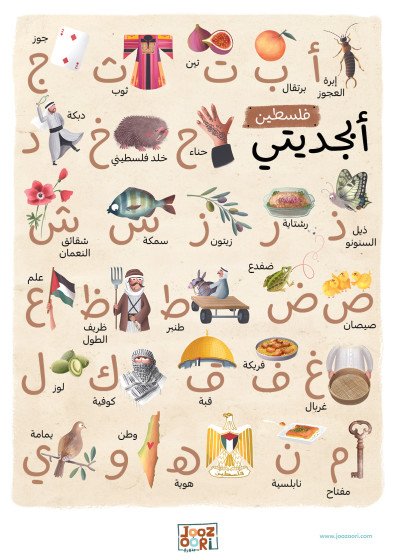

Un éditeur qui crée des affiches et des cartes en mettant en valeur la richesse linguistique et culturelle des pays arabes

Focus sur les éditions Joozoori

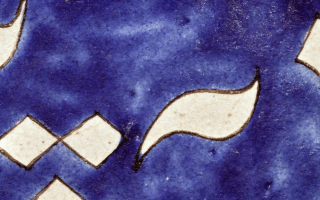

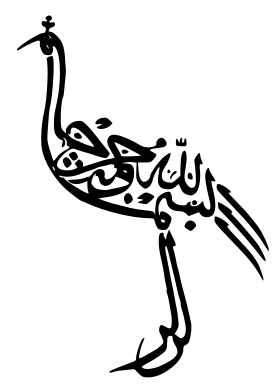

Dans le cadre de l'exposition “Ecrire ou calligraphier?”, à l'IMA jusqu'au 21 septembre

Focus sur la calligraphie arabe

Venir à l'IMA

Institut du monde arabe

1 Rue des Fossés Saint-Bernard, 75005 Paris

- Métro : Ligne 7, Jussieu ou Ligne 10, Cardinal Lemoine

- Bus : Lignes 24, 63, 67, 86, 87, 89

- Vélib' : Stations n° 5020, n°5019, n°502

- Parking : 1, rue des Fossés saint Bernard, 75005 Paris